The Daya Bay Reactor Neutrino Experiment Begins Taking Data

| Institute of High Energy Physics , Chinese Academy of Sciences |

|

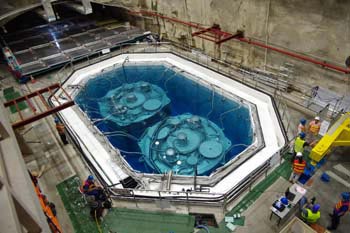

| The antineutrino detectors |

The Daya Bay Reactor Neutrino Experiment has begun its quest to answer some of the most puzzling questions about the elusive elementary particles known as neutrinos. The experiment's first completed set of twin detectors is now recording interactions of antineutrinos (antipartners of neutrinos) as they travel away from the powerful reactors of the China Guangdong Nuclear Power Group in southern China.

The start-up of the Daya Bay experiment marks the first step in the international effort of the Daya Bay Collaboration to measure a crucial quantity related to the third type of oscillation, in which the electron-flavored neutrinos morph into the other two flavored neutrinos. This transformation is due to the least-known neutrino "mixing angle," denoted by θ13 (theta one-three), and could reveal clues leading to an understanding of why matter predominates over antimatter in the universe.

The Daya Bay experiment is well positioned for a precise measurement of the poorly known value of θ13 because it is close to some of the world's most powerful nuclear reactors - the Daya Bay and Ling Ao nuclear power reactors, located some 55 kilometers from Hong Kong - and it will take data from a total of eight large, virtually identical detectors in three experimental halls deep under the adjacent mountains. Experimental Hall #1, a third of a kilometer from the twin Daya Bay reactors, is the first to start operating. Hall #2, about a half kilometer from the Ling Ao reactors, will come online this fall. Hall #3, the farthest hall, about two kilometers from the reactors, will be ready to take data in the summer of 2012.

The Daya Bay experiment is a "disappearance" experiment, powered by the enormous quantities of electron antineutrinos produced in the nearby reactors. The detectors in the two closest halls will measure the raw flux of electron antineutrinos from the reactors. The detectors at the far hall will look for a depletion in the expected antineutrino flux. The cylindrical antineutrino detectors are filled with clear liquid scintillator, which reveals antineutrino interactions by the very faint flashes of light they emit. Sensitive photomultiplier tubes line the detector walls, ready to amplify and record the telltale flashes.

A relatively small number of these interactions, over a thousand a day out of the millions of quadrillions of antineutrinos produced by the reactors every second, will be captured by the twin detectors in each near hall. Due to their greater distance, the four detectors in the far hall will measure only a few hundred a day. To measure θ13, the experiment records the precise difference in flux and energy distribution between the near and far detectors.

The experimental halls are dug deep under the mountain to shield the detectors from cosmic rays. The antineutrino detectors are submerged in pools of water to shield them from radioactive decays in the surrounding rock. Despite shielding, some energetic cosmic rays make it all the way through; their trajectories are tracked by photomultiplier tubes in the walls of the water pool and "muon trackers" in the roof over the pool. Events of this kind are ignored in collecting the antineutrino data. After two to three years of collecting data with all eight detectors, the Daya Bay Reactor Neutrino Experiment intends to meet the goal of measuring the oscillation amplitude of θ13 with a sensitivity of one percent.

China and the United States lead the Daya Bay Reactor Neutrino Experiment, which includes participants from Russia, the Czech Republic, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The Chinese effort is led by project manager Yifang Wang of the Institute of High Energy Physics, and the U.S. effort is led by project manager Bill Edwards of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and chief scientist Steve Kettell of Brookhaven National Laboratory.